the performance of writing

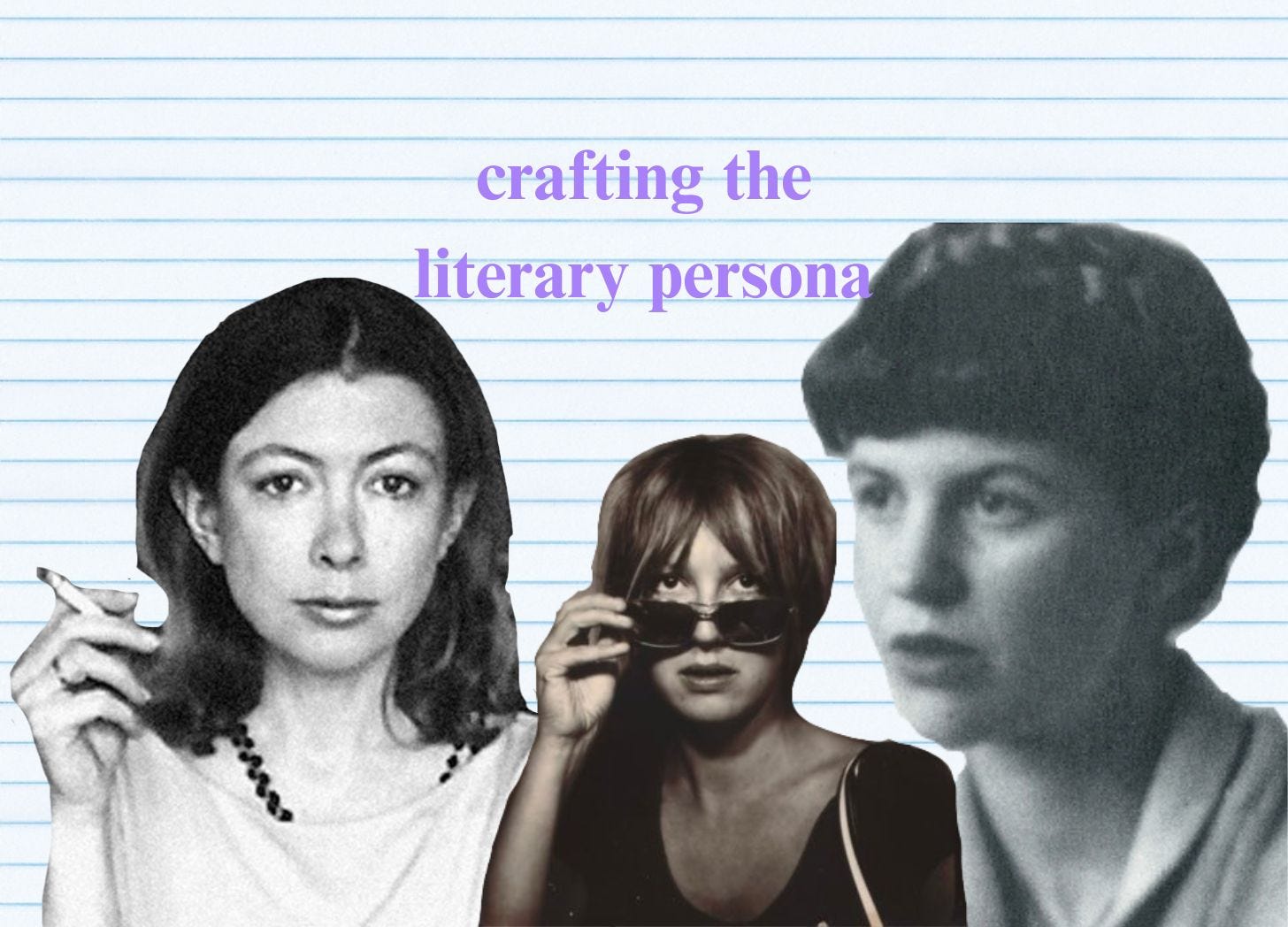

crafting the literary persona, the ethics of posthumous publication, the decline of privacy and the pressure to perform constantly

Growing up, I wrote journal entries as if an invisible entity was reading them. Styling them like an epistolary novel, I sprinkled in details about my life to provide necessary context, like I was introducing myself to the entity instead of just writing my thoughts down. The entity wasn’t just a reader; they were also a critic, there to judge me as a person and, more importantly, a writer. I wanted the entity to like me, think I was cool, and think that my life was interesting, but most of all, I wanted them to think my writing was good.

Though I didn’t have words for it then, I was trying to form my literary persona. Every writer has one, intentional or not. The best ones tend to be meticulous with theirs. Writers who craft memoirs, personal essays, and autofiction have personas that are intrinsically linked to their work and the audience they want to gain. Eve Babitz, for example, was primarily known as a muse and party girl of 1960s/70s Los Angeles, always on the arm of some famous musician, actor, or artist. She used her position as a participant of hedonistic West Coast culture to craft the literary persona of a woman who will let you experience the fantasy of L.A. through her and surprise you with sharp, witty observations and passionate defenses of her hometown. She was sexy, cool, and smart, intriguing readers with her many colorful stories that may or may not be slightly exaggerated. Who’s to know? The fun is in guessing.

Depiction of the self for an audience is inherently a performance, from the information you choose to share in a memoir to the language/style you use in your writing to the “casual” photo dump you post on social media. The ideal isn’t to lie but to present sides of yourself that will get your point across and attract readers. Even if you bare your soul, if it’s for an audience, it’s part of your persona. The most gifted writers are honest in their work but still have a clear line between their persona and their person. Joan Didion is a great example of this, writing memoirs about heartbreaking, personal moments such as losing her husband suddenly and deconstructing the grief that followed. Yet she writes with detachment and clear style, only providing the details that are necessary to complete the work. You finish her memoirs knowing such intimate moments of her life, but it doesn’t feel like she’s oversharing either, at least in my experience.

So imagine my surprise when the news broke that the late Joan Didion’s journals about her sessions with a psychiatrist were being published. The internet went aflame with cries of ethical concerns. Anyone who’s kept a diary imagined their private lives being published without their consent and shuddered. Legally, the journals are “fair game.” But what is fair game to the people who stand to gain something monetarily from this? Tracy Daugherty, Didion’s biographer, who will no doubt see sales of his book spike after this release, said in a statement to The Guardian:

“She was not naive about publishing or human nature… Leaving behind something as rich as this journal promises to be could not be accidental…. She had to know that this journal would be, in her terms, ‘gold’.”

Yes, Didion was aware of her fame. The notes were apparently typed and labeled inside a filing cabinet, not burned or hidden away. Maybe she did have plans to turn them into something one day. But no clear instructions were left. Is the absence of a no enough to warrant their publishing? In that same article, the opinions of Didion’s close friends were in striking contrast, with the consensus among them being that her privacy was betrayed. One anonymous close friend said:

“While I, of course, understand the public thirst for this document, given Joan’s extraordinary place in American letters, Joan was nothing if not meticulous and intentional with the details she decided to share – and not share – in The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights.”

There’s a disconnect about what is being published. According to the publishing world, we aren’t accessing intensely private notes about distressing topics and relationships but “an extraordinary work.” Barnes & Noble’s sales copy uses phrases such as ‘unprecedentedly intimate’ and ‘reveals sides of her that were unknown.’ This is laughably awful. Of course, it’s intimate and revealing because it was private! It’s interesting to note that the journals being published explore Didion’s relationships with her husband, John, and their daughter, Quintana–both of whom are subjects of Didion’s memoirs and are not alive to express their opinions on this publishing. One of the last true literary celebrities, Didion’s work is inextricable from her curated public image. What genuine purpose is there to publish such personal writing that pulls back the curtain that was so carefully sewn?

When Sylvia Plath died, her ex-husband/poet Ted Hughes was granted control of her estate and published Ariel, a finished poetry manuscript. Relatively unknown outside literary circles until this point, Plath’s fame skyrocketed, but at a great cost. Hughes edited Ariel’s poems in a way that cemented the reputation that she was a deeply troubled woman bound for suicide. In 2004, Plath’s original Ariel manuscript was revealed and provided a different, much more optimistic interpretation of the work, but it was too late. The persona she did not craft had long overtaken her person.

Most of Plath’s work was posthumously edited and published by Hughes, and while her talent was recognized, the narrative remained the same. People couldn’t look past the mystery of who the “real” Plath was, intrigued by the story of her tumultuous marriage, shocked by the nature of her death, and hungry for any more writings of hers that could answer lingering questions. In 1982, Hughes published her diaries. But these were heavily edited. Like, entire sections and pages just gone. Hughes even admitted to losing and destroying some diaries. After Hughes died in 1998, an unabridged version came out, made of 60% unpublished material edited by Plath’s children, who wanted her exact words to be known after years of blatant censorship. Now, people got to see Plath for who she really was–a brilliant, clever, funny writer with a zest for life.

As much as I enjoy the unabridged journals, it still feels like a guilty peek behind the curtain that Plath wasn’t alive to sew. Their publication shouldn’t have been necessary. The Plath Persona was due to Hughes’s gross mishandling, but also because people didn’t bother to look hard enough at the work Plath published while alive. Despite Plath fans, scholars, and biographers working overtime to rehab her image, The Bell Jar still has a reputation of being something only girls who’ve worn grippy socks read. Semi-based on Plath’s life, people take it at surface-level as another example of her unwell psyche. Yes, it is frank about mental illness, but it’s also much more. The main character strives for purpose and independence in a world of rigid gender roles, sexism, and misogyny. Like with Plath’s version of Ariel, the ending is more optimistic, completing the tale of a three-dimensional modern woman. And to be frank, men have been getting away with writing the most depressing, insane, deplorable shit for years and never got judged, dismissed, or boxed in the way Plath has.

There is no singular ethical statement to be made for all posthumous publishing. Anne Frank’s diary is one of the best resources we have for Holocaust history, even if the thought of Anne knowing millions of people have read her private thoughts makes my stomach turn a little. Emily Dickinson’s legacy is undisputed, though her work was heavily edited and censored to hide her feelings for a woman. Franz Kafka ordered his remaining papers to be burned, but they were published instead, creating a lasting influence coined as “Kafkaesque.” Years may have passed, and history may have been made, but the fact remains that we will never know how an author feels about the work that was published after they died. Their peers may have published with good intentions, recognizing the value of their work and not wanting it to go ignored, but we will never know how they’d feel about receiving that recognition, if they even wanted it in the first place.

There’s no use lamenting the publication of Emily Dickinson; she was alive 140 years ago and her work is here to stay. As for Sylvia Plath, I guiltily admit I’d give anything for that supposedly missing journal to turn up. But for someone like Joan Didion, who recently died in 2021, the option remains to think critically before publishing anything. With such a strong legacy behind her already, it’s not about honoring Didion’s memory or sharing her brilliance with the world. It’s about mining a writer for content. When a writer has done their job well, it’s natural for people to crave more. Hell, I pray every day for a new Elena Ferrante novel. But, especially for writers like Didion, whose work is a direct extension of themselves, we must understand the toll that can take. Sifting through your personal life to find the next memoir or essay can feel like selling yourself out instead of just selling yourself. A persona can protect you if you’re mindful of what to share and how to share it. To see people disregard that and demand more is an affront to a writer’s privacy and craft. Viewing everything a writer writes as potential content damages the writer and their artistic process. The search for the “real” Didion, Plath, etc., should not go beyond what they have approved for the public. We don’t need to know the “real” writer; that’s not for us. The persona a writer presents should be enough. The work they publish should be enough. Respect what they have presented, and don’t ask for anything more.

During my creative writing degree, the importance of having a “personal brand” was drilled into us. “Persona” and “personal brand” are used interchangeably, but to me, persona encompasses not just how a writer presents to the public but also the style in which they write. A personal brand is mostly what it sounds like: a marketing tool. In the time of Didion, Babitz, and co., the things that boosted your personal brand were interviews, the occasional reading, photos you chose for author bios or magazine spreads, and your behavior in the public eye. Now, it’s mostly about social media. Unless you’re Sally Rooney, a worldwide best-selling author with no social media presence, if you’re trying to get your work out there, you’re probably thinking a lot about algorithms, portfolio design, the perfect bio, or the best caption to go with your latest photo or reel. With traditional publishing not having the money for marketing power that it used to, many authors feel forced into the role of “content creator” just to promote their work.

This can potentially have disastrous results. It’s hard for everyday users not to get caught up in social media trends, constantly thinking about their aesthetic or the way they think strangers perceive them. Social media post-influencer takeover wants everything to be presented in neat, digestible packages to sell a product or lifestyle. The knowledge that this is done to sell us something doesn’t take away the pressure to participate in it. Especially for people who do have something to sell, such as their writing. When social media is your marketing tool, it’s difficult not to blur the line between you and your persona or swing in the opposite direction and create a persona that’s far removed from who you are in an attempt to attract an audience. You view everything you post from the perspective of a stranger you want to attract, which isn’t inherently bad–it’s part of crafting your persona, after all–but when unchecked, this auto-voyeurism1 can go so far as to affect your writing.

The pressure to perform used to seep into my personal writing. I gave up writing my journal entries like an epistolary novel, but I didn’t stop acting like they’d be read one day. I found myself crafting my journal entries to produce the perfect snippet to share on social media, complete with cute, curly handwriting, my journal positioned in a spot that would show off what’s on my nightstand so people could see I was a Cool Girl with Taste. Every entry I made, I thought about how it sounded, what it made me look like as a person, what parts of it could be made into a viral Substack quote. I wondered about Plath’s journals, how they were written so beautifully with poignant observations and glittering descriptions. She didn’t know her journals would be published one day–this writing was just for her, and yet it’s better than what many people will publish in their lifetimes. Am I even a good writer if my journal entries don’t measure up? Shouldn’t my journal be practice?

Now, I vehemently reject this. My personal writing is nothing like what I publish. It’s almost too simple, something a child could read, nothing more than a brain dump of everything I’m feeling and thinking. No rhyme or reason. No attempts at poignancy or flowery-sounding descriptions. No self-editing. I don’t bother to make the handwriting legible. My words turn into scribbles, nearly falling off the page. I finally write what I can’t say out loud, removing the pressure to make any of it publishable. From my journal’s perspective, I’m probably the most insufferable woman on Earth, but that’s okay because it’s only for my eyes. It’s helped me learn the value of privacy instead of trying to make every thought and experience I have into a Substack essay. I refuse to journal as if hungry executors want to leech off of me and publish it one day. I’m not saying this will ever be a likely scenario, you don’t have to humble me. But for me, part of crafting my persona is knowing what to keep private and freeing myself from the pressure to constantly perform.

The “real” me, as far as you’re concerned dear reader, is the me I put on the page.

Thanks for reading! Have you ever thought about the personas of your favorite writers? What does crafting a literary persona look like for you? Besides the personas of the writers I mentioned, one writer’s persona I currently love is that of Marlowe Granados. In a world where the term “literary it girl” can be both a compliment and an insult, Granados is unapologetic in her glamorous style and confidence, here to ditch the notion that party girls can’t be serious writers (because even after the rise of Eve Babitz, misogynists are still having that debate).

If you liked this piece, consider liking it, sharing it, and subscribing to my newsletter for free. To see what I get up to when I’m not writing, you can follow me on Instagram at mjewrites.

loved this so much, i often think about music being released post humous and what the art means if it wasn't ever approved by the artist themselves. do we understand what they were trying to convey or what someone else wanted to convey?

I think a lot of what you wrote about here is part of why I stopped writing. I can't seem to get other people's perceptions of me out of my head. Every time I write, I can't help but imagine it from the perspective of my readers (or worse, someone who knows me lol).

Also, what you said about worrying over even your writing in your journals measuring up to Plath's is also EXACTLY what goes through my mind. It's honestly so hard to get our of your own head and just write. I think I got good about it for a while, but now I'm back to the constant self-editing. How do you get past that? if you don't mind me asking

ps. I LOVE the pic you made. it's such a vibe. what did you use to make it?