melancholy and the writer

when melancholy and existentialism are your biggest influences and worst enemies, fighting the urge to quit, and avoiding making the Depressed Writer your identity

A journal entry from October 7th, 2022:

“I think something must be wrong with me. I should not be this sad. The sadness comes in waves. It enters my mind in the mornings like the sun filtering through my blinds. I am fine only when I can distract myself long enough to remind myself there’s more to life. There are moments when I’m fine. Happy. Hopeful.

But the sadness lingers and I think a sick part of me wants it to. Sadness is my strongest feeling. It inspires me. In a way, it makes me feel alive more than happiness does, sometimes.”

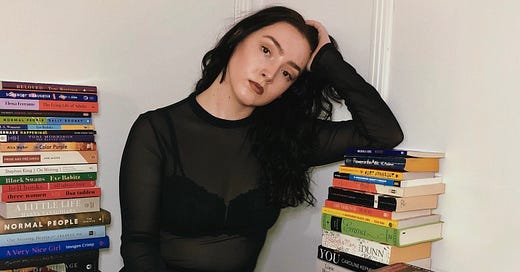

Like many writers, when I am feeling sad or when something bad happens to me, I think about how I can use it in my writing someday. While I’ve always been creative and have had a fascination with reading and telling stories from a young age, I didn’t seriously start writing until I was 13. Like any teen girl, I was crushed under the weight of intense and often conflicting emotions and I needed somewhere to put them. So I started writing very bad poetry in my scrappy composition notebook, scribbling down several entries a day on everything from depression, self-harm, suicidal ideation, and how much my life sucks.

Even on days when I felt on top of the world, I would go home and write from a place of sadness or angst. The novel that made me decide to seriously pursue writing is The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky, perhaps the best young adult novel that captures the concept of feeling happy and sad at the same time. When I was 17, I idolized Effy Stonem of Skins with her mental illness romanticized as alluring nihilism, making boys her playthings as they chased after her, trying to “figure her out.” I would scroll on Tumblr to see aesthetic pictures of Prozac and self-harm scars and wanted desperately to romanticize my own mental health issues and create something out of them. Like many other chronically online teenagers at the time, I didn’t understand the harm in romanticizing my mental illness. Tying this together with my proclivity for writing, creating something from my own despair became a part of my identity.

There is a reason sadness brings about great art. The art says what we are too afraid to say out loud because sadness goes hand in hand with vulnerability. Many of the greatest poets and writers in history have made melancholia a prominent mood or subject in their works; Emily Dickinson, Edgar Allen Poe, Sylvia Plath. Don’t get me started on Shakespeare. There’s a reason why Greek tragedies are still so popular today. Hell, even Lana Del Rey, Mitski, and Pheobe Bridgers are included in my book. It’s no secret that sadness, in any form, for any reason, fuels many an artist and feeds many a consumer.

But when writers are surrounded by so much melancholia, from the media we consume to our own thoughts and feelings, and use it as a source of inspiration, how do we not let it consume us? As writers, we are prone to questioning everything in this life, trying to understand why people feel what they feel and do what they do. It’s necessary for us to fall into these thought spirals in order to write something that speaks to humanity. But at what point does it become unhealthy?

Jean-Paul Sartre writes in Nausea:

“My thought is me: that's why I can't stop. I exist because I think… and I can't stop myself from thinking. At this very moment - it's frightful - if I exist, it is because I am horrified at existing. I am the one who pulls myself from the nothingness to which I aspire.”

While the narrator in Nausea is simply referring to the existence of his own consciousness, I think existentialism, melancholia, and writing go hand in hand. This is a very dangerous combination for someone like me who has a tendency to linger in her sadness, ruminate on everything and repeat this cycle until I get a moment of levity where I can exist as a regular person in the world, not a wandering ghost witnessing the world’s daily operations but stuck in my own plane of existence, not able to fully engage. I don’t mean to sound like I think I’m some tortured Great Artist afflicted with the pain of thinking ~deeply~ about everything (because I am definitely not), but one must think a lot in order to create, and when the inspirations for your creativity come from melancholic and existential thought patterns, it can become easy to get trapped in a hellish cycle. There’s a reason why the ‘depressed writer’ is a popular stereotype, and writers are often believed to be more prone to depression and anxiety because they are natural examiners of the world and think and feel with intensity.

Even when writers aren’t sourcing their creativity from melancholia, we are subjected to it externally. Due to the nature of our craft, we spend a lot of time in isolation, working long hours slumped over our laptops and staring at blank screens until we’re begging just to be able to write a sentence. The pay is unstable and the future is bleak. We pore over our work, wondering if it’s good enough. No matter how much we’ve been trained to take criticism, every rejection hurts because we’ve spent half the time in self-pitying flagellation and the other half reveling in the rush of endorphins from creating something we think is finally good enough. And the cycle repeats. We are our biggest doubters and get in our own way more than anyone else. At least, this is my experience.

Everyone is familiar with writer’s block but writer’s melancholia is something else entirely. In her article ‘When Writers Melancholy Approaches, Return To Your Base’, Sarah Thomas defines writers’ melancholy for her as an inability to connect with her work; she feels hopelessness, a void. I’d say it’s the same for me and I imagine it’s that way for a lot of other writers as well. A lot of times, I’ll read over a draft and wonder what I’m even trying to say. I’ve even been doing that right now with this piece. I wonder if any of it is good enough. I wonder if there’s a point to it all. I wonder if I’m just wasting time.

Lately, with the draft of my novel, I’ll work myself up to finally opening the document, only to feel a mounting existential dread once I do, which manifests in scrolling the internet under the guise of “research” and rewatching or rereading my novel’s sources of inspiration until I’ve deemed it acceptable to quit for the day and try again tomorrow. Only to rinse and repeat.

Sometimes I think about quitting writing altogether. It feels like an uphill battle, trying to consistently create without losing my mind. Maybe I would live a more peaceful life. Or maybe I would be miserable, always thinking about what could’ve been. Either way, no matter how long I go without writing, the desire is there. I can only describe the desire to write as being pulled by puppet strings, yet I am somehow both the puppet and the puppet master.

A couple of quotes from one of my favorite writers, Sylvia Plath, from her published journal, The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath:

“I have the choice of being constantly active and happy or introspectively passive and sad. Or I can go mad by ricocheting in between.”

“And by the way, everything in life is writable about if you have the outgoing guts to do it, and the imagination to improvise. The worst enemy to creativity is self-doubt.”

When many people think of Sylvia Plath, the first thing their minds go to is her suicide. She is then entered into the evergrowing list of Depressed Writers. Her untimely demise then retroactively defines her personal and professional life. She becomes less of a person and more of a persona. This is unfair to her work and to her memory. Her most famous work, The Bell Jar, is a raw depiction of mental illness. Much of the novel is sourced from her own life, including her suicide attempt at 19 and hospitalization. But the novel ends on a hopeful note. Her journals explore the struggles of writing but they also explore the drive that keeps her writing in the first place. To ignore this duality in her work is to ignore the reality of life itself; that life is both melancholic and cheerful.

Obviously, we can’t ignore the reality that many writers do experience depression, addiction, and several other mental illnesses that can leak into and be exacerbated by their chosen craft. But as writers, we don’t have to let those issues define us or our writing, even if our writing is sourced from the most unhinged thoughts and emotions we can muster. And as readers, we must be wary of defining writers solely by the subjects of their work.

I am most drawn to melancholy, existentialism, and introspection in what I consume and what I create. I think I will forever be ricocheting in between active and happy and passive and sad, but I do have some control. I can pour all of my thoughts and emotions into a body of work and recognize that it is a part of me but also separate from me, a living being of its own. It does not have to define me. I am the puppet and the puppet master, after all.

Mary, It feels like you pulled these thoughts and ideas right from my head. What an amazing essay!