is the handmaid's tale the extent of your feminism?

my problem with referencing popular dystopian novels online

The finale of Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale recently aired, and though I have not kept up with the show since 2021, I constantly see it mentioned in the comments of social media posts about the U.S.’s increasingly violent agenda against women’s rights. Phrases such as “we’re living in the handmaid’s tale”, “the handmaid’s tale warned us about this” and “blessed be the fruit” (a phrase spoken in the show) have become shorthand among women in the U.S. to express their fear and frustration online.

In case you’re unfamiliar, The Handmaid’s Tale is based on Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel of the same name. It follows a woman named Offred (“Of Fred”) who lives in a future version of the United States, renamed Gilead, that operates as a Christian totalitarian, theonomic, militarized society where fertile women are forced into sex slavery to provide children for the elite. These women are called Handmaids, and while no women in the world of Gilead have equal rights, the Handmaids are among those who have it the worst.

The first season aired in 2017 just a few months after Trump 1.0. Though much of it was written before the election, the timeliness of its release was lightning in a bottle. The show quickly garnered comparisons to Trump’s America, inspired countless think pieces both pro and against these comparisons, and sparked women’s rights protests, with many protestors donning the iconic red robes the handmaids wear. From the beginning, this show was touted as a warning for women in the U.S. Look what could happen if we let the fascists win. Eight years later, after the show’s six-season run and in the midst of a second, far worse Trump term, not much has changed.

I used to take part in the internet shorthand, retweeting “blessed be the fruit” and feeling like I shared secret knowledge with my fellow women. It was a way for us to say to each other “you see what’s going on here too, right?” without having to explain. Now, whenever I see that phrase or something similar, I have to resist the urge to roll my eyes. It’s like sharing poorly made infographics or tweeting “fuck Trump” and patting yourself on the back for appearing like a good activist on the internet. It’s like Democrats incessantly tweeting “he can’t do that!!!!!” instead of actually doing something to take a stand. It’s like sharing horrible news stories every day to your friends and followers who already align with your political beliefs (I will admit I’m sometimes guilty of this, I think there’s a fine line between sharing information and circle jerking about what good leftists you are). You’re not changing anything by being chronically online. I may be taking this too seriously, but when people apply fictional references to real life politics in the comments of TikTok, it more often than not reflects a shallow understanding of the source material and the situation they’re trying to apply it to. And in the case of The Handmaid’s Tale specifically, the source material is problematic to begin with, and that’s why we should stop referencing it all the time.

Margaret Atwood has clearly stated that nothing in her book is purely fictional. Every occurrence of sexism, discrimination, violence, etc. is pulled from a real life situation. So how do you write a dystopian story about a far-right Christian totalitarian America with real life events if that hasn’t happened yet? You steal the stories of women of color. While Atwood has stated that the rise of far-right conservative Christian ideology in 1980s America inspired the novel, she also looked to places like Iran, Cambodia, and the Philippines, with Iran’s 1978 Islamic revolution being a direct reference and even mentioned in the novel itself. In interviews, Atwood has also compared Gilead to Afghanistan.

In Atwood’s own words, The Handmaid’s Tale is a response to the belief that totalitarian, oppressive, religious regimes in other countries would “never happen here [in North America].” You could say that Atwood is acknowledging that Western white women need a narrative that centers themselves in order to recognize what’s been happening to women of color since the beginning of time, but I hesitate to give her that credit. Instead of amplifying the voices of the brave women who have been fighting for their rights for longer than any of us have been alive, she took their stories and applied them to white women and conveniently ignored the religious far right’s natural inclination towards white supremacy.

In the novel, Black and Indigenous people are done away with in a few sentences, suggesting they were exiled and murdered. Black people are known as “Children of Ham” which is a reference to Bible passages from Genesis that were used to justify slavery of Black Africans. Herein lies the story’s central problem of white feminism that the TV show has only worsened. In the book and the show, the white women face experiences that Black women in America have faced for centuries. Many of these scenarios are directly pulled from slavery and segregationist eras, such as being denied a surname, or taking the surname of their enslaver once emancipated, forbid to read and write, and denied the right to vote.

How can you suggest the probability of this totalitarian society without acknowledging its very real roots in slavery and white supremacy? The people who run Gilead would absolutely keep people of color as slaves because their very literal interpretations of the Old Testament would demand it. The TV show, in trying to have some diversity, has only exacerbated the book’s issues. While white women are still the primary characters, women of color are also handmaids in Gilead and that just doesn’t seem plausible, even for a society with dangerously low fertility rates. These people would not want non-white babies unless they can use them as slaves. What’s interesting is that this narrative issue could’ve been solved because another class of human beings in the story is the Marthas, house servants who are infertile or too old to produce children and are therefore deemed only fit for labor. The show’s decision to include diversity without addressing the very plausible outcomes of a theocracy based on racism once again puts white women in the center.

What many people still don’t seem to realize is how all of these issues are connected. In white, patriarchal societies, fascism is inherently sexist, misogynistic, and racist. The first wave of anti-abortion sentiments in the U.S. was fueled by nativism and eugenics, not morality or religion. It was feared that white Protestants would be outnumbered by Catholics, immigrants, and people of color, so the movement pushed for women to have as many children as possible, a movement now pushed by far right Christians and politicians. Under fascism, people who are considered “undesirable” will still have a purpose to fulfill for the elite. As it happened during slavery, anti-abortion movements ensured that Black women could keep producing human capital for their enslavers while white women could produce more white children, especially white boys who would grow up to become white men who could vote and hold positions of power. In the modern day, this would translate to more Black people and people of color to be exploited in underpaid jobs (or become slaves in the for-profit prison system) while white people continue to benefit from and uphold oppressive systems.

Something else I want to touch on is the lack of transgender characters in The Handmaid’s Tale. While queer people were deemed “gender traitors” and either executed or turned into handmaids, there’s not a single trans or non-binary character in the novel or the show. In later seasons the writers have stated how they wrote current events into the show, so with the rise of anti-trans rhetoric in the U.S. and the U.K., wouldn’t it have made sense to show a non-binary or trans character? They couldn’t have all been murdered, but even if they were, an acknowledgement of their existence would not only be appreciated but also required for a story that once again prides itself on being based on real life. Marginalized people have always experienced fascism, even in so-called “liberal democracies.” No matter their good intentions, stories like The Handmaid’s Tale only reinforce the idea that it’s a problem worth caring about when it happens to white women.

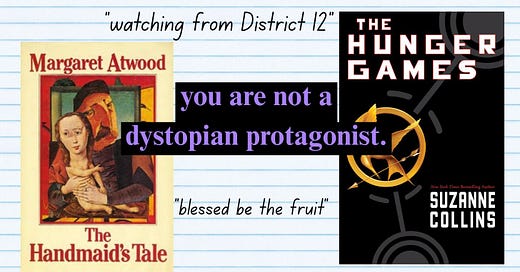

Another popular story I see being shallowly referenced on the internet is The Hunger Games. Phrases such as “watching this from District 12” have become popular internet shorthand for criticizing the elite, particularly influencers at the Met Gala. This TikTok by sadajewels pretty much sums up my feelings on that matter, but nevertheless: I will criticize rich people all day every day, but the Met Gala is a fundraising event for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, not just a party for the elite to show off their fancy clothes. The Costume Institute relies on this funding to conserve and show art, and given that the internet loves to defend anti-intellectualism, the preservation of art is needed now more than ever. In the world we live in, if you want to raise enough money, you need eyes, and celebrities bring eyes.

Commenting “watching from District 12” on your iPhone from the comfort of your bed is not criticizing wealth inequality, much like commenting phrases from Handmaids isn’t dismantling patriarchy. You are not living in poverty in District 12, you are not a sex slave in Gilead. Things are scary right now, I won’t deny that. Trump 2.0 is certainly closer to Panem or Gilead than before. But we are not there yet and whatever the country looks like in the next few years, we still won’t be, because these universes are fictional. I don’t want to totally bash the use of these phrases because in the right context they can provide some brief comic relief or vent deeply rooted fears and frustrations with a short, easily recognizable reference. But it seems that parroting these phrases on the internet is taking the place of real community and activism, and preventing us from applying these stories in the real world.

I think stories like Handmaids and The Hunger Games can be useful in learning how fascism can take over, especially for young readers who need an introduction to those topics. But even if they have roots in reality, these stories are fiction. I think they’re great starting points for learning, but tweeting shallow references that commonly misinterpret the works they’re referencing isn’t going to dismantle the system. I get just wanting to rant on the internet. I’m literally doing it right now. I have to stop myself every day from incessantly posting about the horrors. Because it does no good. We’re all aware. To be clear, social media can be a great tool for activism and spreading awareness. But most of the time, I don’t see it being used that way. To quote the endlessly quotable essay ‘blips and bloops and oofs or lacks thereof’ by Griffin of briffin glue huffer, “we need to have conversations with each other and not the algorithm. the left needs to get offline.”

If you want to learn how to survive fascism, the answer isn’t going to come from a dystopian novel. It’s going to come from the people who have already lived through it. You want to know how religion is used to control people? Watch Shiny Happy People. You want to understand how the religious far right rallied around Trump in 2016? Read Jesus and John Wayne. Crack open some bell hooks, Audre Lorde, and Annie Ernaux for intersectional, feminist, and socialist theory and memoir. Read accounts of slavery, genocide, and colonialism from non-Western sources. Shit, at this point, get a VPN and read from news sources outside America. Study the parts about Nazism and the Civil Rights Movement that schools don’t teach, because that’s where the real stuff is. Sorry (not sorry) but it’s a bit hard to take you seriously if your only frame of reference for feminism is a white-washed dystopian novel. Please, just read anything else.

Thanks so much for reading! If you liked this post, please like, comment, share, and subscribe for free if you wish. To see what I get up to when I’m not writing, you can follow me on Instagram at mjewrites.

Bringing the heat today! I have a piece in progress that I didn’t know how to write but it explores the idea that reading might make us “empathetic” but also less likely to take literal action because the act of reading/consuming tricks us into thinking we’ve done something productive towards solving an issue. This sounds very similar to what you are getting at here and I love it. I’m guilty of using those phrases as a secret feminist language because it’s easier to be cynical than face harsh reality head on, isn’t it? Making me think today…. !